Background

Environment is rarely static - temperatures rise and fall, food availability changes - all demanding an organism to sense the surroundings and make proper responses. Therefore stress response is critical for survival and fitness. At the same time, however, environment may change abruptly, or may experience long-term shifts, e.g. a steady increase in global temperature. In both cases, the existing stress response may become malfit.

The goal of our lab is to understand how gene regulatory networks for stress responses evolve and how it may have contributed to species adaptation to its environment.

To achieve this goal, we study a group of evolutionarily related, yet ecologically diverse species of yeast, including the well-known eukaryotic model organism, S. cerevisiae, and a related commensal and opportunistic pathogen, C. glabrata.

Specific aims

Our current research is focused on the following specific questions:

How does the structure of stress response networks evolve between related species?

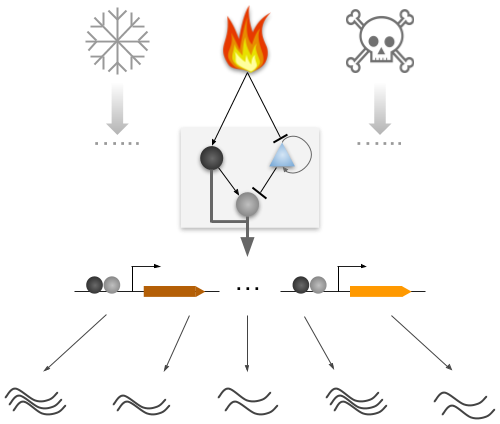

We will comprehensively map the gene regulatory networks for major stress responses in commensal and related free-living species. Using conserved master transcription factors for each stress as "handles", we aim to uncover the underlying target network and compare them both at the level of network structure and downstream functions.What types of changes (protein, promoters or chromatin states), and in which part of the network, underlie the evolution of stress response networks?

As an example, our previous work in the Phosphate Starvation Response network identified the master transcription factor Pho4 to have evolved and acquired additional targets in the commensal yeast C. glabrata. We will study how protein sequence changes in Pho4 led to the expanded target set.How might the changes identified above contribute to species adaptation to their environment?

Not all changes between species are adaptive. Most, in fact, are results of "neutral evolution". To identify those changes that may have been involved in species adaptation, we will investigate the physiological and fitness consequences of the regulatory network changes. We also apply evolutionary sequence analyses to identify signatures of selection in both protein coding and regulatory DNA.

Approaches

functional genomics, e.g. RNA-seq and ChIP-seq; molecular evolution (DNA sequence analysis) and phylogenetic approaches; phenotypic and fitness assays

Relevance for human health

By dissecting the differences in their stress response regulation and the underlying evolutionary history, we hope to better understand the challenges faced by commensal microbes and the strategies that proved successful by natural selection to allow them survive and thrive in that environment. This will lead to new perspectives on the relationship between host and commensals, including when and why they switch to the pathogenic mode -- a stress response from the microbe's perspective -- and will likely give rise to new theraputics and preventative measures for fungal infections.